Everyone always thinks about the future. The complexity and uncertainty of our time are forcing us to do so in order to respond effectively and efficiently to unexpected events. But how do we create a “desirable future” in which companies can respond to new needs in an agile and innovative way, operate sustainably for people and the environment, and – of course – be financially successful in the process?

It’s easy to say “think outside the box” but much harder to actually do it. Many managers get stuck in their “old-school thinking” based on unconscious beliefs and assumptions that hold them back from doing different things and doing things differently. If they continue on this trajectory, they inevitably create a future that really is just a continuation of the past. Real transformation cannot take place if we do not make a conscious effort to investigate our “unconscious bias” – meaning how our knowledge, values, and experiences shape the way we think, solve problems, approach innovation. So before something truly new can emerge, we first need to take a step back and become aware of how our thinking shapes our behaviour and ultimately our future on a personal, organisational, and societal level.

Thoughts vs thinking

A first important distinction here is to separate thoughts from thinking. Thoughts are the ideas that are created non-stop in our mind, including memories (of past things), plans (for future things), as well as interpretations and evaluations (of current things) through sensory impressions we gather in the moment.

As you read this article, your mind is producing thoughts. You might be remembering similar articles. You might be thinking about what you could do with what you’re reading right now and whether it’s worth to continue or do something else instead. As you notice these thoughts, you immediately evaluate them which creates an emotional resonance (e.g. I thin this text is interesting / boring). You produce thoughts without having to tell yourself to do so – and most of the time, we are not even aware what we’re thinking. We just do it.

Put simply: Thoughts are WHAT your mind produces. They are the result of the thinking process. If you are meditating, you know how crazy it is to simply observe what’s going on in our head at all times, and how difficult it can be to actively stop the thought generation process for a while…

Now, how is thinking different from having thoughts?

Thinking can be seen as the process of evaluating thoughts and interpreting sensory inputs (e.g. what you can perceive through your five senses in the moment). This process heavily depends on our past experiences as they shape the way we make sense of new information.

For example, you may observe a team member and immediately evaluate their behaviour as positive, negative (or neutral), without consciously choosing to do so. Or imagine that a problem arises – the first thing you do is to think about possible solutions by drawing on existing knowledge and experiences you gathered from problems of similar nature you have faced I the past. The same goes for the colleague expressing an idea to you – without actively deciding that you are now going to evaluate the idea he/she just presented, you automatically engage in an unconscious evaluation process that immediately makes you judge whether you think this idea is good or bad.

But how often do we question our thinking itself and focus on cognitive bias? How frequently do we then take a step back and ask: “How can I be sure that this idea is actually good / bad?” Often, we don’t consider our own blind spots as we think that the way we see the world is ‘the only right way’. We ignore the taboos that may limit what we allow ourselves to think and do, the beliefs we unconscious took on through social conditioning, and the assumptions we make based on what we know. Do you know what worldview underlies your (fast) thinking? (PS: Check out Daniel Kahnemann’s book “Thinking, Fast and Slow” for more details on this topic).

Our present thinking is determined by our past experiences

Knowledge, experience, beliefs, assumptions – all of them are products of the past. They may help us solve future problems or generate innovation. Maybe the new problem is similar to an old problem you were able to solve and you can draw on your existing knowledge to better solve the new challenge in front of you.

But what if the problem is radically different in nature? And what if the context in which this problem arises has changed dramatically?

Imagine the following:

A sailing boat sets out to explore new territories. There is a crew that works on the ship, led by one captain. Everyone in the crew has a specific role based on their experience, knowledge, and skills. The structure is hierarchical, and little communication is needed to control the ship. Everyone knows what they are doing since they are familiar with. All activities together allow the ship to sail smoothly. This is the familiar context for the sailors.

Now, the ship gets into a storm and the crew gets stranded on an unknown island. Suddenly, new skills are needed since the crew needs drinking water, fire, shelter, food – and ideas on how to get off the island. This represents a completely new context for the sailors. Skills that were previously considered unimportant, such as the need for communication and decentralised collaboration now become essential. Every idea counts, and it doesn’t matter who has it. Even the youngest crew member can make an important contribution if he or she has an idea, for example about how to find drinking water.

This new context requires both: New thoughts – and new thinking. What worked on the ship or at home doesn’t matter here. Many managers have not realised yet that the winds are turning. A storm of change is right on the horizon, and signs of upheaval are there. The breeze is picking up and the waves are rising higher. New competitors are entering the market, customer needs are constantly changing, social and economic trends are becoming increasingly influential, and we’re facing one global crisis after the other. If these signs of a change in circumstance continue to be ignored, and managers don’t acknowledge that NOW is the time to develop new skills, this may have devastating consequences for the business.

But since the the real storm (crisis) is (still) missing, there is simply not enough urgency for most leaders to change.

When we don’t see a need to change ourselves (and our thinking) because we don’t (yet) see it as a matter of survival, it can be a very difficult to do so. That’s why people (still) try to meet entirely new problems and challenges with proven patterns of thinking by drawing on existing knowledge, experience, beliefs and assumptions to navigate the new challenges.

Radically different and innovative approaches and ideas are often (unconsciously) rejected or fought against because we are all creatures of habit. We like if things stay the same and we can do what we’ve always done. From a biological perspective, this preserves our energy and thus makes us more likely to survive (at least, that’s what our subconscious mind is telling us). Thus, doing new things is an energy expense and we naturally want to avoid it. However, what we have to realise is that if we DO NOT invest our energy into changing, we will likely not make it.

But that’s not the only fallacy: We also have to overcome our tendency to believe that the past behaviour that has made us successful will no longer make us successful now. That can be really hard to get your head around, but it is necessary in order to allow new thoughts, to question your established way of thinking, and to examine the underlying belief system we use to make sense of the world.

A new idea can be a breakthrough, even though it contradicts all of our past experiences around what ‘works’. It may even evokes negative feelings such as the fear of failure, leading to deep resistance. Whether we choose to face or avoid this fear, both is uncomfortable. However, only one of both options will allow us to adapt, evolve, and ultimately, survive.

Making unconscious thinking conscious

Facilitators deal with the phenomenon of unconscious bias in workshops all the time. New ideas arise within the group, and immediately they are evaluated (aka judged) in a positive or negative way. The role of the facilitator – as well as every leader – should now be to make the thinking process that is taking place on a meta-level transparent by asking the following questions:

❓What kind of challenge are we facing here, and can it be solved with existing knowledge, skills, and experience? (conscious analysis)

❓What experiences, beliefs, and assumptions make me evaluate this idea positively or negatively? (cognitive bias) Check out the 50 cognitive biases of our modern world

❓What feelings emerge when I evaluate with this idea? (emotional bias)

❓Where do these beliefs, assumptions, and feeling come from? (subconscious analysis)

Asking these questions requires all participants to reflect on their own thinking and unconscious ways of evaluating information. Doing so can significantly enhance the ideas and decision that are generated and made within a team.

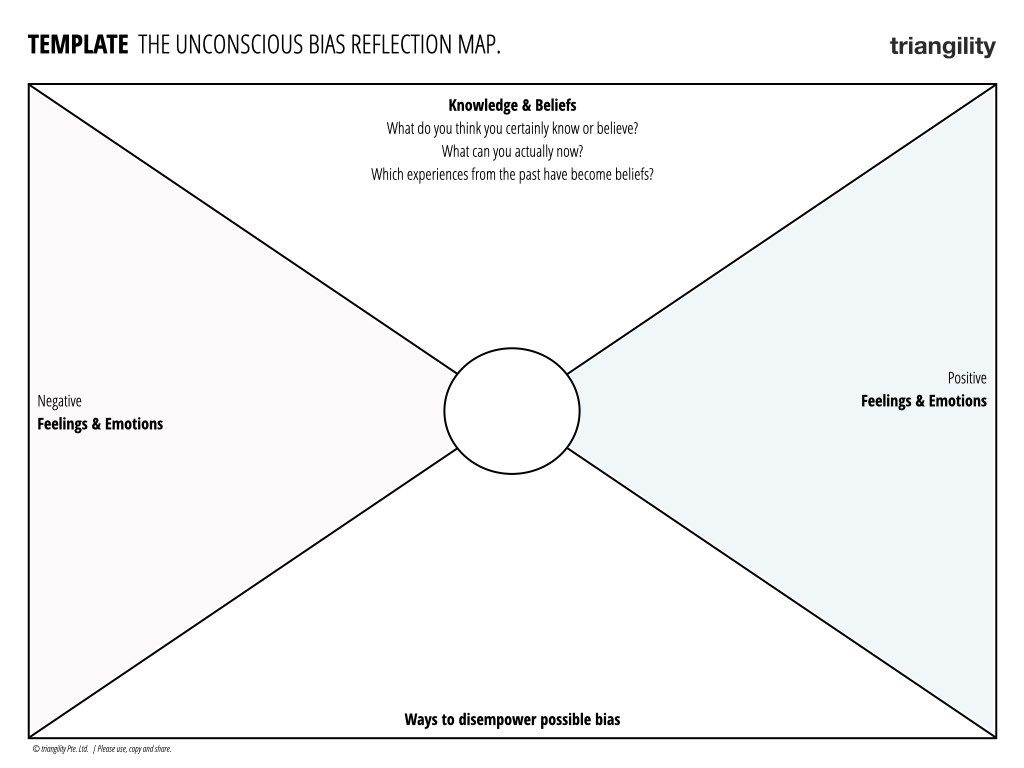

To make the unconscious conscious, we have developed a special tool called The Unconscious Bias Reflection Map that you can download for free.

It’s works based on the well-known analogy of the iceberg: The much larger part of what determines our thinking and actions is unconscious. A person or a group can only change what becomes conscious – and what one begins to talk about. What is needed is a dialogue that invites and integrates the different perspectives of everyone on the team, without differentiating between wrong/right or good/bad.

This can be particularly challenging where status plays a role: People with high status exert greater influence on a group – their valuations are given greater importance, and their ideas have a greater chance of being accepted by the group – even when they are obviously not the best. In this case, a leader might decide not to participate in a process of problem solving and decision making, and instead allow a facilitator to work with a group / team to ensure that the group can think and co-create breakthrough ideas without mental and emotional blockages that allow them to truly shape a new and better future, rather than a continuation of the past.

Because:

When the context changes, we have to change. And this starts with our thoughts (what we think) and thinking (how we think).

Further resources:

Download our Unconscious Bias Reflection Map and how to apply it (Description)

Mit dem Laden des Videos akzeptieren Sie die Datenschutzerklärung von YouTube.

Mehr erfahren

Watch the training video on Unconscious, Cognitive and Emotional Bias and a brief introduction to the Reflection Map.